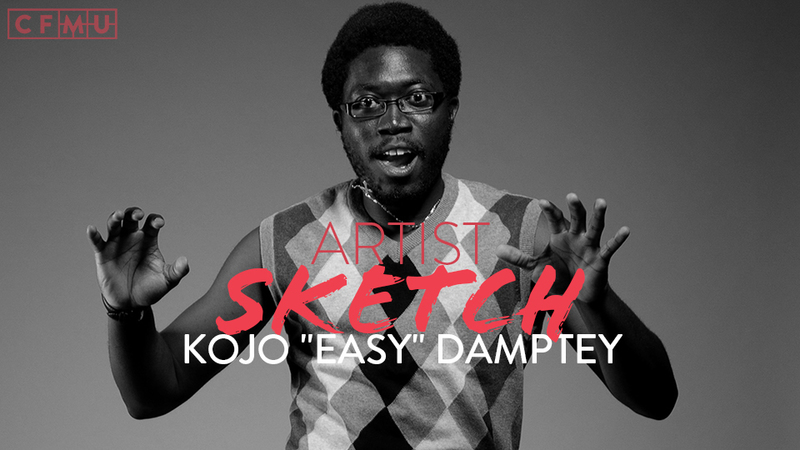

What I Want to Tell the World: Kojo "Easy" Damptey - CFMU Artist Sketch

PHOTO: George Qua-Enoo

Ask people this question: what local artists do you know? Now, don’t ask music fanatics or local scenesters - they have an unfair advantage. Ask random people at the supermarket, or that tall woman at the bus stop, or that guy who always eats his lunch on the bench outside your office window. Average folks, if they can answer at all, will likely respond with artists such as the Arkells, or Terra Lightfoot, or Tom Wilson, or Teenage Head. Which makes sense. They’re all stellar.

They’re also, for the most part, guitar-based rock’n’roll artists. Hamilton has always been considered “a rock’n’roll town.” Dig a little deeper, though, and you break into a whole other strata. Electronic artists, hip-hop emcees, jazzheads, experimental performers, reggae bands, soul singers, funk players, African drum enthusiasts; they’re all here. It’s just that, sometimes, they have trouble getting from here to there. There being the stage. The spotlight. Your ears.

After arriving in Canada at the age of seventeen, Kojo “Easy” Damptey decided to become a musician. When he started to perform, there weren’t a lot of footsteps in which to follow. He referred to his style as “Afro-soul” – a combination of highlife, pop, jazz, reggae, hip-hop, soul and more. Who did you emulate, where did you play? It wasn’t as if he could get a gig at the local African music club. It didn’t exist.

Day by day, gig by gig, Damptey found his way. Now he hopes that he’s left enough of a trail that others can follow in his footsteps.

PHOTO: George Qua-Enoo

Determination and independence were bred in Damptey from a young age. Even coming to a foreign country as a teenager (along with schoolmate, fellow musician and former Hamiltonian Kae Sun) didn’t rank as the biggest obstacle of his young life at the time. “In Ghana, high school is boarding school,” explains Damptey. “You always have to leave home, so the concept of being independent, finding stuff for yourself and hustling and all those things was like, yeah. If you can live in boarding school in Ghana you can live anywhere in the world!”

Damptey attended Colombia College for a year, and then completed a Chemical Engineering degree at McMaster. It wasn’t a career path he was destined to take. Back in Ghana, he and already developed a taste for music and the music business. “When I was in elementary school or just middle school, I remember [recording] my own DJ thing over a Bob Marley cassette,” he laughs. The cassette, unfortunately, belonged to his father. “That didn’t sit too well! But then that’s how I got interested in recording and music.”

After arriving in Hamilton, Damptey’s first forays were more hip-hop and sampling related. Later, he decided he wanted to turn the tables, and, as he jokes, “make music where people will sample me.” He started to learn piano and compose his own music. One of the largest influences on Damptey’s sound was (and still is) Highlife, a modern style of Ghanaian music, based on the structures of a traditional music called Akan but played on modern instruments. It was the perfect vehicle for much of what Damptey wanted to express.

WATCH: Kojo "Easy" Damptey performs "Giants" LIVE

“Highlife was always supposed to be about storytelling, describing what was going on in the community,” Damptey explains, “so that’s how my music is. Then African music always has rhythm because if you’re going to be talking about things happening in the community you have to make sure you keep peoples’ attention, and rhythm is part of doing that.”

Damptey surrounded himself with talent – his band consists of Mohawk and Humber music grads who he describes as “so well-versed in music and put their own spin on things - it’s not just me all the time.” In 2013, they recorded Damptey’s debut, Daylight Robbery. Daylight Robbery is a big, bright record, “a record that would get people’s attention.” If Daylight Robbery was a bold artistic introduction, though, Giants – his second and most recent - is a bold artistic statement. As the title suggests, it is filled with stories of existence, resilience and resistance, celebrating cultural heroes from Africa, the Middle East, Latin America and Indigenous societies.

“It is what I want to tell the world,” Damptey says of the album. “More in depth, more political, more in your face, and also experimental in a way. It’s more me. If you were to look down into my musical soul, that’s basically it.”

It’s difficult, at times, to imagine where Damptey finds the time to make music at all. He spends much of his time advocating for music. Some of that is for Hamiltonians in general, as with his work on the Hamilton Music Advisory Team. “People don’t see the work (chairperson Mark Furukawa) he puts in. I know that the team doesn’t have power to change things drastically but with the advisory role that we have, I think we’ve been able to do some good things.”

It is what I want to tell the world... If you were to look down into my musical soul, that’s basically it.

- on Giants

LISTEN: Kojo "Easy" Damptey's sophomore album, Giants

Much of Damptey’s musical advocacy, however, is for music outside of Hamilton’s penchant for rock’n’roll guitars. Having made inroads to the local music scene, he realized he could use some of his experience to guide others. It started the with annual Renaissance Festival, which was founded as a platform for artists of colour and diverse musical styles.

More recently, Damptey launched his own record label, Celestial Voodoo. Along with local musician Scott McIntosh, they have created a home for music that is also outside of traditional guitar-based rock’n’roll. The label has released Damptey’s recent record as well as albums by Shanika Maria and the Beelays. He says that, quite often, labels won’t know what to do with a certain type of artist, perhaps because the music is a fusion of genres. “Sometimes they don’t understand. Well, we understand,” Damptey laughs.

...African music always has rhythm because if you’re going to be talking about things happening in the community you have to make sure you keep peoples’ attention, and rhythm is part of doing that.

Damptey is also a founding member of COBRA – the Coalition of Black and Racialized Artists - along with other local musicians such as Mother Tareka and Kobi Annobil from Canadian Winter.

“Kobi and I would get together and start talking about how hard it is to make music in this city,” Damptey recalls. “Was it just us? Then we realized other artists were saying the same thing; it’s not just specific to music, it’s specific to people of colour doing visual art or theatre or whatever arts discipline they’re in.”

COBRA is a resource for racialized artists; Damptey describes it a “vehicle.” “If you’re an artist of colour and you do anything send it to us and we’ll promote it, he says. “We [also] go to institutions that are not representing the artistic spectrum of our community to suggest some solutions.” COBRA has begun to make concrete, positive changes in the Hamilton artistic community. Since they launched, the AGH has exhibited some of the art of COBRA members, which Damptey believes wouldn’t have happened without COBRA’s engagement.

If you’re an artist of colour and you do anything send it to us and we’ll promote it...We go to institutions that are not representing the artistic spectrum of our community to suggest some solutions.

- on COBRA (Coalition of Black and Racialized Artists)

We know that Hamilton, like many other cities, has its share of horrific problems and challenges. It can be difficult to read the news sometimes. Though it may sound idealistic, Damptey believes the people who can lead the way forward are the artists – artists like himself, artists like Mother Tareka and Lee Reed. They encourage him to keep moving and continue his mission and his music.

“The non-traditional artists in Hamilton are always socially conscious, but we tend not to listen to them,” Damptey says. “If we did, we probably wouldn’t be in this state. You listen to Tarek’s music, you listen to Lee’s music - some of our critiques might be harsh, but they’re harsh because we’re also living it - and we love this city the same way that everyone else does.“

Photo: George Qua-Enoo

Some of our critiques might be harsh, but they’re harsh because we’re also living it - and we love this city the same way that everyone else does.

- on socially-conscious artists in Hamilton

Artist Profile and Extras

Name: Kojo “Easy” Damptey

Releases: Daylight Robbery (2013), Giants: Stories of Existence, Resilience, & Resistance (2018)

Origins: Damptey was born and raised in Accra, Ghana. “Music has always been a thing in our family,” says Damptey. “My dad was always playing different types of music at home. Obviously highlife music - you can’t go wrong with that – but then he introduced me to artists like Chuck Mangione, soul music, and everything they listened to when they were growing up.” The musician in the family was his father’s brother, a pianist who teaches music at the University of Ghana. Damptey began to learn the piano after arriving in Canada in 2001.

On the meaning of nickname 'Easy': “Ah, yeah,” Damptey grins as he explains the nickname. “All I can say is there are two versions of that story. I’ll leave it to the reader to pick out which version they want. The first one is that I’ve always been an easy going person, I talk to people, I try and make sure they’re comfortable. That’s one. Then for those of you that like Snoop Doggy Dog, he had some skits on some of his albums I’ll just leave it there because I don’t think [the content] is appropriate.”

On activism: Damptey has been involved with numerous causes and community action groups, and they’re not always music and arts related. He is also the Manager of Programs with the Hamilton Centre for Civic Inclusion (HCCI). When asked if he considers himself an activist, he suggests that the term, in today’s climate, is almost meaningless. “I’ve always said that you know politics is personal, regardless of what your political spectrum is,” he says. “When decisions are made politically, it’s going to effect you. Whether you’re an activist or whatever, you still have to be engaged politically. We’ve seen that in our province. When cuts come, no one says ‘Oh because you never protested last week, your kids are ok!’”